The Anglo-Scottish War had raged for nearly a quarter of a century. On the last days of summer in 1319, a 10 to 15 thousand strong Scottish army was almost at the gates of York. To make matters worse for the English, their King, Edward II, had marched his army, that included York’s garrison, nearly 150 miles north along the east coast of England to lay siege to Scottish-held Berwick-upon-Tweed.

So, York was defenceless and ripe for sacking, and Edward’s most cherished possession was in imminent peril. If that wasn’t enough, hearts in York sunk as deep as Loch Ness when they learnt The Black Douglas was the vanguard of the two Scottish generals.

For more than a decade Sir James Douglas fought alongside Robert the Bruce, King of the Scots. After the Scottish victory at Bannockburn the people of north England came to know Douglas only too well. His men rode small horses known as hobbins, giving the name of hobelar to both horse and rider.

Douglas’s raids were brutal with crops destroyed and villages burned. In 1318, The Black Douglas recaptured the last Scottish stronghold from the English: Berwick-upon-Tweed. So fearful the English were of Douglas, legend has it mothers would sing to their children:

Hush ye, hush ye, little pet ye.

Hush ye, hush ye, do not fret ye.

The Black Douglas shall no get ye.

Sent him homeward tae think again

In the early years of the war, Edward II’s father – Edward I (Longshanks) – used York as a staging area for many invasions of Scotland. Recognising the town’s location and economic importance to the realm, Longshanks established a permanent garrison. The father was admired as a reformer of English common law and as a brilliant military tactician who gave no quarter on the field of battle and expected none in return. Militarily, the son proved woefully inept.

On 26 June 1314, seven years after ascending to the throne, Edward II saw Robert the Bruce and Sir James Douglas decimate his grand English army at Bannockburn. Before the first taste of battle, the English had a four-to-one advantage. In the words of the Scottish national anthem, Flower of Scotland, the Scots “sent him homeward tae think again”.

Into the heart of England

Now that Berwick was back in Scottish hands Robert knew Edward couldn’t resist trying to retake the castle. Though stocked with troops and supplies everyone was aware the Scots couldn’t hold out forever.

When the English siege on Berwick was finally underway the King of the Scots, whom Edward steadfastly refused to recognise as such, issued orders to Scotland’s two most successful generals – Thomas Randolph, the Earl of Moray, and Sir James Douglas. They were to take their joint armies and cut a scorched-earth swath through the heart of England driving as far south as York. If successful, the diversionary tactic will create dissension within Edward’s army and lift the siege of Berwick.

Douglas and the Earl also planned to capture Edward’s wife, Queen Isabella of France, who was in residence at York awaiting her husband’s, hopefully triumphant, return.

The Scottish mobile infantry successfully penetrated more than 100 miles into England and within striking distance of York. Douglas and the Earl halted their forces on the north bank of the River Swale, near Myton. In the towns and surrounding countryside rumours likely ran amok about the size and disposition of the Scots, the death and destruction they had already inflicted. Perhaps the fearful rumours envisioned the number of horns on their head.

A plan foiled and an Archbishop’s folly

Meanwhile, the plan to kidnap Queen Isabella was foiled when a Scottish spy was captured. Likely not having a good day in the local torture chamber, the poor soul revealed everything. Isabella was quickly transported from York to the relative safety of Nottingham.

In light of the peril confronting them, York’s leaders never considered surrender or asking for terms to save their town. Sir William Melton, Archbishop of York, accompanied by Sir John Hotham, Chancellor of England, and Nicholas Flemyng, York’s mayor, settled on a third and seemingly illogical choice.

They mustered an unskilled militia of bishops, clergy and any man who can carry a stick, then marched north to confront the battle hardened Scots. En route others joined, most of whom knew nothing of combat, and by the time they arrived at Milton-upon-Swale, Melton’s rag-tag band likely outnumbered the invaders.

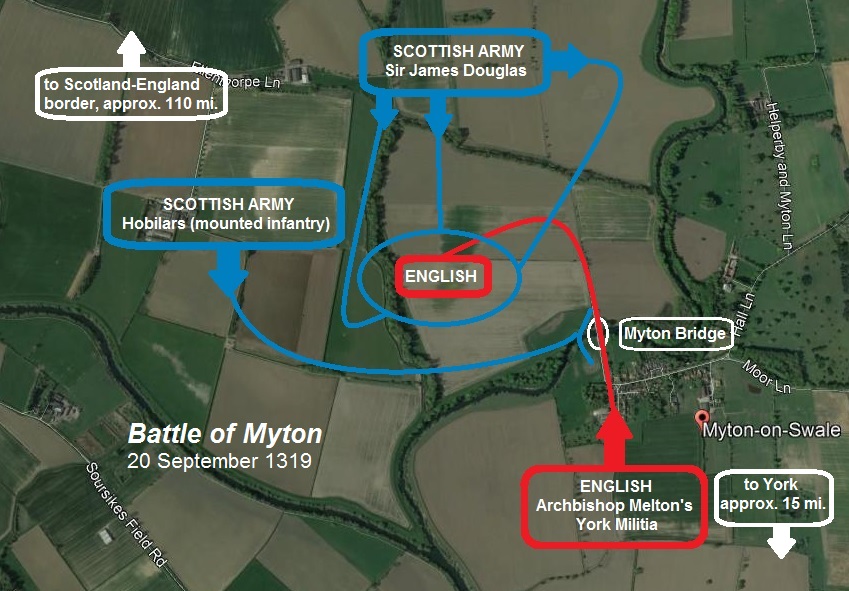

The Archbishop believed his God would carry the day for the righteous men of York. Unfortunately, like his King, Melton was rubbish at battlefield strategy. Instead of forming a defensive perimeter and holding the south end of the only crossing for miles, he marched the men of York across the River Swale bridge, to do battle with The Black Douglas. Every campaign in warfare turns on a single decision that cascades into chaos. This was the Archbishop’s moment.

A victory without glory

The Scots waited in their customary single wedge-division. York’s militia, lacking any manner of battlefield assemblance, stumbled toward the Scottish lines. Nearing close quarters the Scots let loose a terrifying war cry and charged the hapless English.

The Archbishop’s untrained militia turned on their heels and broke for the Myton bridge. Unfortunately, the Scottish hobelars, anticipating the rout, had already executed a flanking manoeuvre and captured the crossing beforehand. Their only access of retreat blocked most of the men of York had little choice but to stand and fight, and mostly die.

Hundreds did manage to make it to the banks of the River Swale, desperate to swim across. The river’s width was not that great an obstacle, yet factor in panic, a fast flowing river and many men who did not know how to swim. Although actual numbers will never be known, by some conservative estimates, 4,000 Englishmen died on the battlefield and another thousand drowned. The archbishop and chancellor escaped. Nicholas Flemyng became the only city mayor to be killed in battle. In York, there were many tears and muffled cries that night.

The battle of Myton was in fact a rout. It held no glory for the Scots.

Job done, a town spared, a King disgraced

When Edward’s nobles learnt of the Scottish invasion and the growing threat to their own homes and property, half of Edward’s army at Berwick-upon-Tweed departed the field. The siege of Berwick ended and became another in a succession of defeats for Edward II. What little remained of his army couldn’t march fast enough from Berwick to save York from imminent sacking, burning, and their families from capture or death.

York, after the slaughter at Myton, was definitely at the mercy of Sir James Douglas and the Earl of Moray. But both were only too aware of how far they were from the sanctuary of Scotland’s lowlands. The English returning from Berwick could move across the north and cut their retreat. Having achieved Robert’s aim to lift the siege of Berwick, the Scottish generals decided to turn their victorious armies homeward. York was spared.

An legacy of two kings

For the next three years, Robert the Bruce and Sir James Douglas conducted lightning raids across the north of England and in 1322, another Scottish army advanced to the outskirts of York. The English were now fearful of a full-scale Scottish assault on the northern frontier.

Truth be told, the Scots were only demonstrating their ability to do so. In fact, Robert did not have the manpower or other resources to capture and hold northern England. Nevertheless, in 1323 at Bishopthorpe, about 3 miles south of York, Edward II finally agreed to a council of truce with his Scottish nemesis.

Two years later Queen Isabella and her son, Prince Edward, journeyed to France on a diplomatic mission where she became the lover of Roger Mortimer, an exiled opponent of Edward II. The next year Isabella had raised a mercenary army and invaded England, which was already in a state of anarchy.

Edward II was quickly deposed, imprisoned and murdered months later.In 1327 The Black Douglas led another successful sortie deep into England and won a preemptive victory in County Durham, at which Edward III was almost captured. Thereafter the two adversaries signed the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton that finally recognised Robert the Bruce as King of Scots, and Scotland an independent country.

First published in Bylines Scotland 21/09/2022

Leave a comment